on

Time, Clocks and the Ordering of Events in Distributed Systems

Have you ever wondered what it takes to tell which event happened before which in Distributed Systems? This concept was examined in Time, Clocks and the Ordering of Events in Distributed Systems paper. It was published in 1978 by Turing Award Winner Leslie Lamport. This paper created a paradigm shift in how we think about Distributed Systems and also became one of the most cited papers in computer science.

Before we dive into the details of this paper, let us first understand the definition of a Distributed System. There are a lot of definitions out there on the web, but let us use the below definition for this blog post.

What is a Distributed System?

A Distributed System is a collection of independent computers which talks to on another using unreliable network and also performs its own tasks. Any system that doesn’t communicate with others and functions on its own is not a Distributed System.

Why does the ordering of the events important in Distributed Systems?

Let us say multiple processes are trying to access one resource which can be used by only one process at a time. A process requesting for the resource must be granted only when there is no other process waiting beforehand to acquire the resource. In such cases, ordering of events globally among multiple processes is necessary to avoid any inconsistencies.

System Clocks

In our daily life, we use the physical time to order events. For example, we say that something happened at 8:15 if it happened after the clock read 8:15 and before it read 8:16. The same can’t be done in Distributed Systems because System Clocks are not perfect and they don’t keep precise time.

- How do computers track time?

- Computers have Real Time Clock (RTC) which is part of the motherboard as an Integrated Circuit and it is responsible for keeping track of current time

- RTC has an alternate power source(Battery) to keep working even when the computer is switched off

- It doesn’t start counting from the current time, it starts counting from the time we set. For example, if we set the time 5 mins behind the current time, then it will start counting with 5 mins delay

- Problems with System Clocks

- Systems Clocks might start counting time from the arbitrary point

- Precision of clock may be affected by temperature, location, or how they are constructed which may cause them to drift away from the current time

In real life, we can say that an event \(a\) happened before event \(b\) if timestamp of \(a\) is before \(b\). In Distributed Systems, we can’t use the physical time to order events because of the above problems. So, Lamport defined a Happened before relation without using physical clocks.

Partial Order

Lamport defined the distributed system more precisely as follows:

- It consists of multiple processes and each process contains a sequence of events.

- Process executing something(Ex: machine instruction, a subprogram, etc.) can be treated as an event.

- Total ordering is satisfied among the set of events in a single process.

- A process can send a message to another process or receive a message from other processes. They are also events.

Let us use right arrow(\(\rightarrow\)) to denote Happened Before relation. By using the above definition, he defined the Happened Before as follows.

The Happened Before(\(\rightarrow\)) relation among the events satisfy the below conditions

- If \(a\) and \(b\) are events in same process and \(a\) comes before \(b\), then \(a \rightarrow b\)

- If \(a\) is message sent by one process and \(b\) is a receipt of the same message by another process, then \(a \rightarrow b\)

- If \(a \rightarrow b\) and \(b \rightarrow c\), then \(a \rightarrow c\)

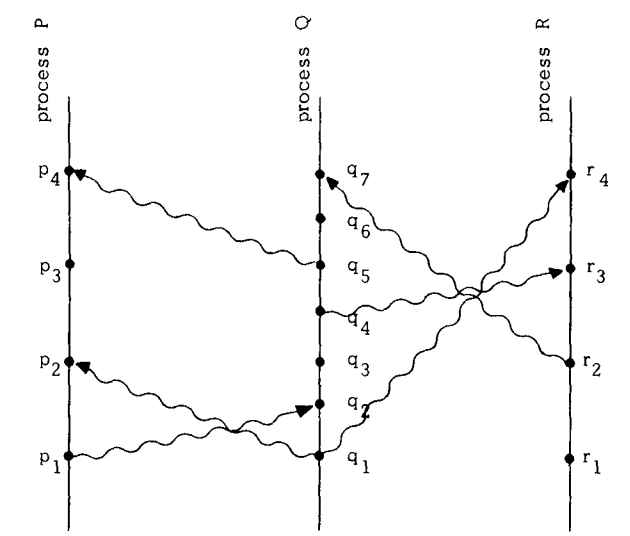

Two different events \(a\) and \(b\) said to be concurrent, if \(a \nrightarrow b\) and \(b \nrightarrow a\). For any event \(a\), \(a \nrightarrow a\). This means that Happened Before(\(\rightarrow\)) is irriflexive partial order (Irriflexive, Anti Symmetric and Transitive) on set of all events in system. Another way of viewing the definition of \(a \rightarrow b\) is to say that it is possible for event \(a\) to casually affect event \(b\).

In the above image, vertical lines are individual processes, dots are events, wavy arrows are messages, and time increases from bottom to top. \(p1 \rightarrow p2\) because they occurred in the same process. \(q1 \rightarrow p2\) because q1 is message sent by process \(Q\) and \(p2\) is receipt of same message by process \(P\). \(p1 \rightarrow r3\) because \(p1 \rightarrow q2\) , \(q2 \rightarrow q4\) and \(q4 \rightarrow r3\). Because time is increasing from bottom to top, \(q3\) seems to have happened before \(p3\) if we consider physical time. But we treat them as concurrent events in this system because there is no causal relationship between them.

Logical Clocks

Now let us order the events in the system according to Happened Before(\(\rightarrow\)) relation using logical clocks. A logical clock is a way of assigning a number to an event which can be thought of as the time at which that event happened. Let us define a clock \(Ci\) for each process \(Pi\) as a function which assigns a number \(Ci(e)\) to each event \(e\) in that process \(Pi\). System of Clocks can be represented by \(C\) which assigns a number \(C(b)\) for any event \(b\), where \(C(b)=Cj(b)\) if \(b\) is an event in process \(Pj\).

We can evaluate the correctness of logic clocks using the Clock Condition. For any two events \(a, b:\) if \(a \rightarrow b\) then \(C(a) < C(b)\). For example, logical clock must satisfy the condition \(C(p1) < C(r3)\) for \(p1 \rightarrow r3\) in the above image. Also, for every \(a, b\) if \(C(a) < C(b)\) then it doesn’t mean \(a \rightarrow b\). In the above image \(C(q3) < C(p3)\) but \(q3\) and \(p3\) are concurrent and not casually related.

Clock Condition is satisfied if the following two conditions hold:

- If \(a\) and \(b\) are events in same process \(Pi\) and \(a\) comes before \(b\) then \(Ci(a) < Ci(b)\)

- If \(a\) is message sent by one process \(Pi\) and \(b\) is a receipt of the same message by another process \(Pj\), then \(Ci(a) < Cj(b)\)

Logical Clock Algorithm

- Each process \(Pi\) increments the clock between every two events by at least one tick

- Each message \(m\) contains the timestamp \(Tm\) at which the event was sent. Process\((Pj)\) which receives the message computes the receipt timestamp using the formula \(\max(Tm, Cj(m))+1\)

Our Logical Clock algorithm satisfies the Clock Condition which means it is consistent with Happened Before(\(\rightarrow\)) relation.

Ordering events totally

- Order the events by using the logical times at which they happened. If there any two events with same logical time, break ties using process id.

- We define total ordering relation \((\implies)\) as follows. If \(a\) is an event in process \(Pi\) and \(b\) is an event in process \(Pj\), then \(a \implies b\) if and only if either \(Ci(a) < Cj(b)\) or if \(Ci(a) = Cj(b)\) then \(Pi < Pj\).

Lamport’s Algorithm for Mutual Exclusion in Distributed System

Let us say there are a fixed number of processes trying to acquire a resource and only one process can use the resource at a time. So the processes must synchronize themselves to avoid any conflict. This is nothing but a variant of the mutual exclusion problem.

We have to come up with an algorithm that grants the resource to a process that must satisfy the below conditions

- The process which has been granted a resource must release it before it can be granted to any other process

- Different requests for resource must be granted in the order in which they requested

- Every process which has been granted a resource will eventually release it, then every request is eventually granted

Why can’t we have a centralized scheduler to synchronize among processes? The centralized scheduler won’t satisfy the second condition.

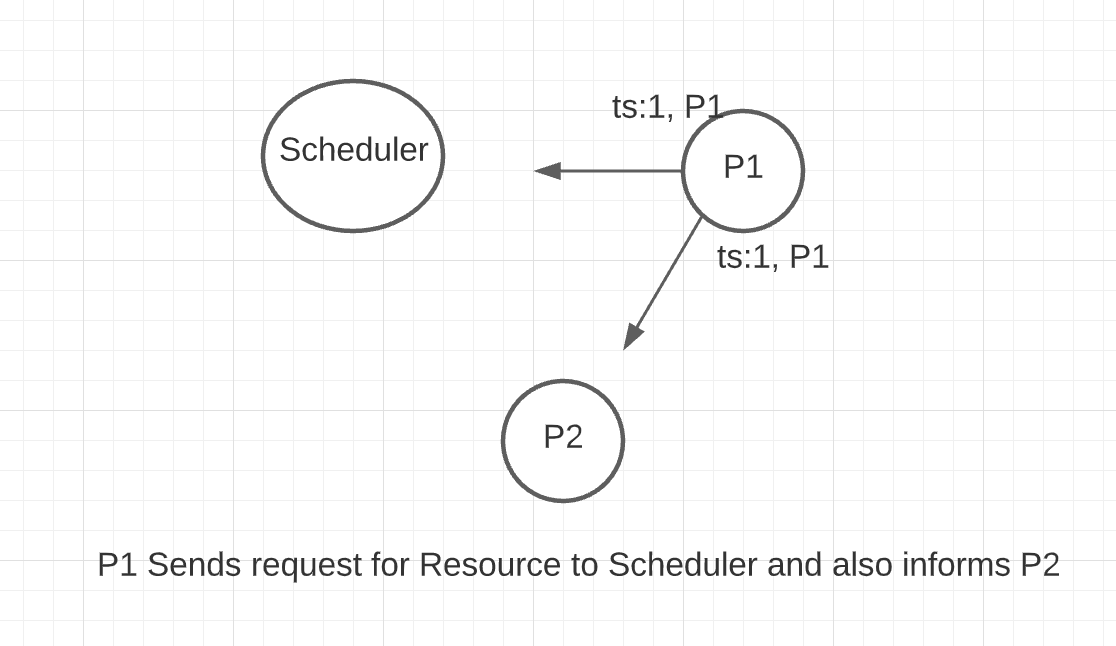

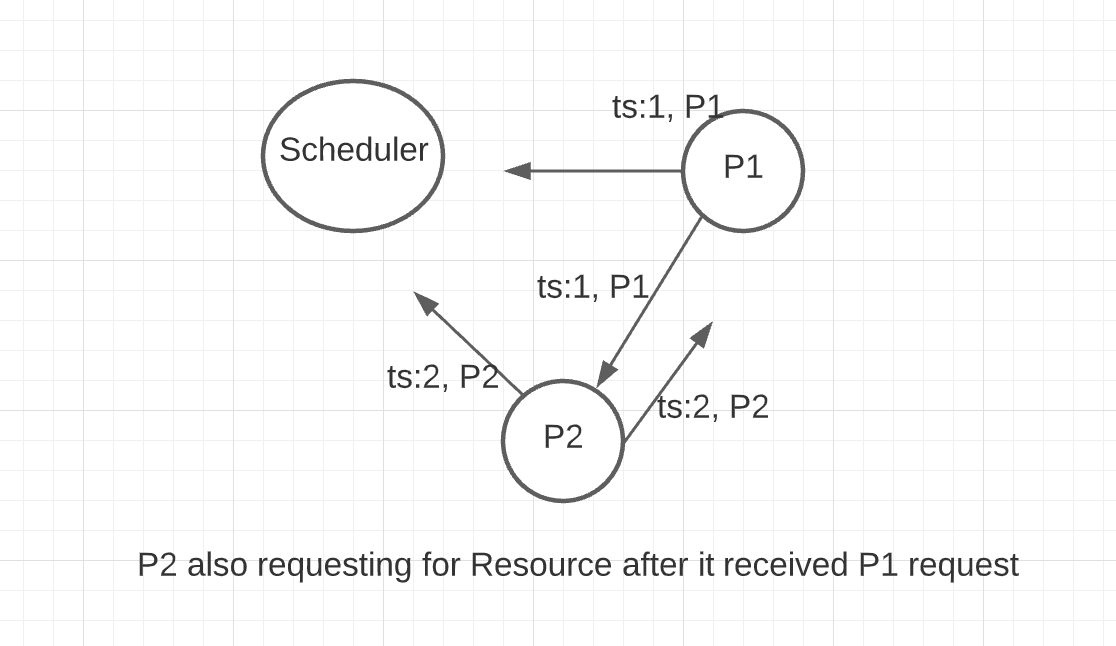

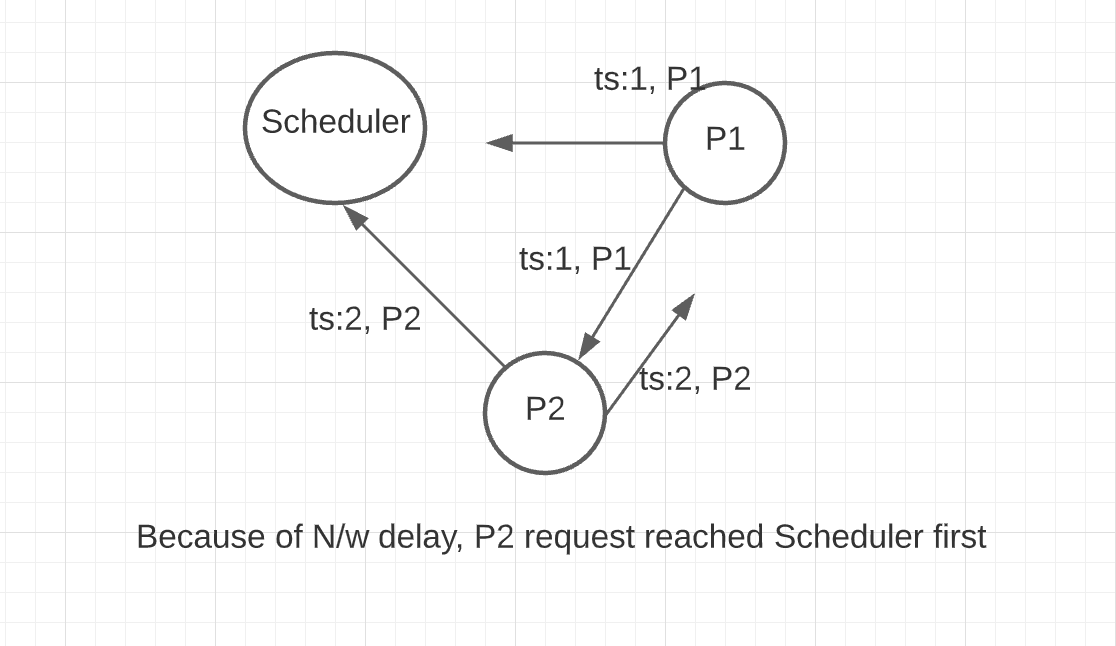

Let us look at the following scenario:

- Process \(P1\) requested for the resource from the scheduler and also informed the other processes about its request.

- After receiving the message from Process \(1\), Process \(2\) also requested for the resource.

- Because of network delay, Process \(2\) request reached the scheduler first and resource has been granted.

- Second condition is violated because the resource has been granted to process \(2\) even though Process \(1\) requested first.

We can solve this problem by using Lamport’s Logical clock algorithm which gives the total order of all request and release operations. Before moving forward with the solution, let us make some assumptions

- Each process maintains a request queue that can’t be seen by other processes

- Every message is eventually received

- For any two processes \(Pi\) and \(Pj\), the messages sent from \(Pi\) to \(Pj\) are received in the same order in which they sent

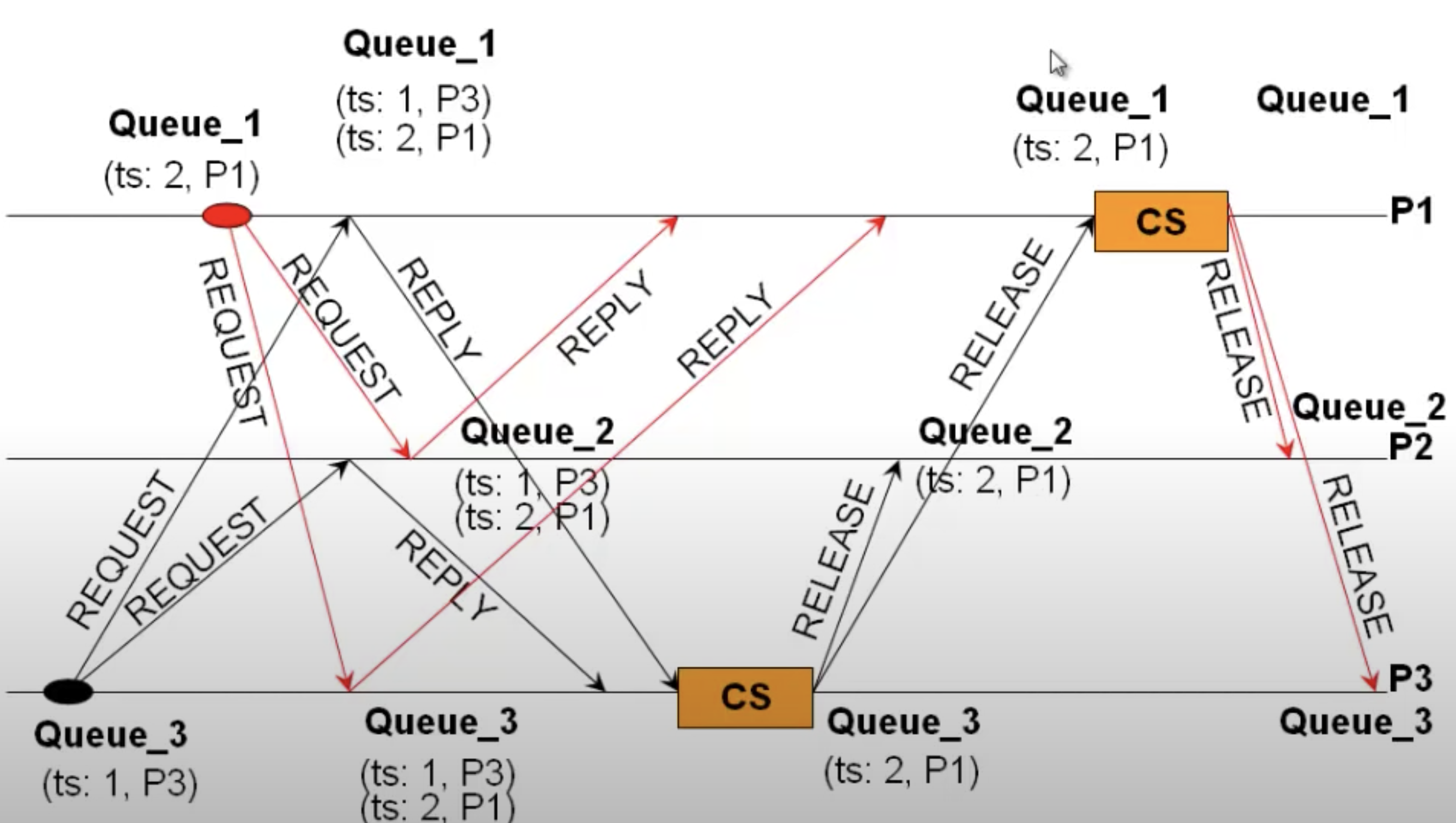

The algorithm is defined by the following 5 rules:

- To request a resource, process \(Pi\) send a request resource message \((Tm,Pi)\) to every other process and adds the request to its queue. \(Tm\) is the timestamp of that message

- When a process \(Pj\) receives a request resource message \((Tm,Pi)\), it adds that to its queue and sends a timestamped acknowledgment to \(Pi\)

- To release a resource, process \(Pi\) removes request resource message \((Tm,Pi)\) from its queue and sends a timestamped release resource message \(Pi\) to every other process

- When a process \(Pj\) receives a timestamped release resource message \(Pi\), it removes any request resource message \((Tm:Pi)\) from its queue

- Process \(Pi\) is granted a resource when the following two conditions are met:

- It has a request resource message \((Tm,Pi)\) in its queue which is ordered before any other request in its queue according to \((\implies)\) relation

- It received a message with a later timestamp than \(Tm\) from all other processes

Conclusion

- Physical clocks are not perfect and they don’t keep precise time

- Happened Before(\(\rightarrow\)) among all events in Distributed System defines an irreflexive partial order

- Lamport Logical Clock can be used to extend partial ordering to arbitrary total ordering

- We were able to solve a simple synchronization problem by using total ordering among events